Jim Woods

|

Jim Woods wrote novels and short stories, many of which stand

alone, while others are assembled into collections, in

worldwide milieus. He was a world traveler, having researched

numerous exotic locales as settings for his stories. Much of

his world travel was for big game hunting which, coupled with

his background as editor with Petersen’s Hunting, Guns & Ammo

and Guns magazines, frequently allowed him to bring firearms

into play in his tales. Jim Woods passed away October 8, 2012;

he lived and wrote in Tucson.

Learn more about Jim at:

http://users.dakotacom.net/~jwoods

|

New Title(s) from Jim Woods

Click on the thumbnail(s) above to learn more about the book(s) listed.

|

|

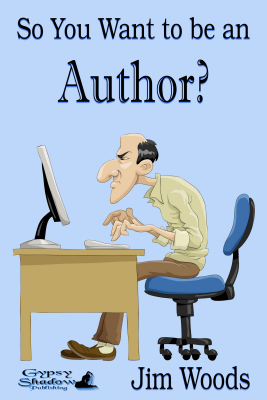

English usage and grammar textbooks, at least

those volumes when in paper print, are so big, so heavy…so

complete. Students toting books and laptops in backpacks need

relief, just as home authors can use more space on their

reference bookshelves. So, You Want To Be an Author? takes up

little space and weight but most importantly provides immediate

answers to questions about grammar, spelling, punctuation and

writing style. No searching through voluminous chapters in

textbooks or scrolling incessant computer files. Pick a subject

and go right to it for realistic examples of literary usage

drawn from the author’s more than four decades working both

sides of the editorial desk. Let his experience as magazine

Editor, Managing Editor, Editorial director; independent book

editor; and his four hundred articles and thirteen books as a

fellow author, be your compact and shortcut guide along the path

to literary success.

Excerpt

Word Count: 31,000

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

| |

|

|

These accounts of shooting birds and hunting

big game mostly relate the author’s adventures in North

America—Canada and The United States. Game species encountered,

or hoped to encounter, include mule deer, whitetail deer,

blacktail deer, pronghorn antelope, elk, bear, turkey and geese.

But by convenience, and necessity because all his hunts don’t

fit neatly into the confines of North America, and the author

had no other place to tell a couple of unique hunt stories, this

volume also includes reports of dove hunting in Honduras and red

stag in Spain. Mainly, this collection tells the story of one

hunter who just happened to be a writer and whose job sometimes

required him to go hunting, making him, if not a PH

(professional hunter) then perhaps a PTPH (part-time) or a SPH

(semi). Either way, for him it was a dream job.

Excerpt

Word Count: 35000

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

|

|

|

Three separate women with separate stories; all

with guns, all with a mission. Marlene as “The Husband Hunter”

had a husband but couldn’t keep him, but found him after years

and a global search, and then didn’t want him... alive.

Veronica simply was misguided; her sole and desperate interest

was protection of her family against imagined evils, but she was

set straight following a neighborhood encounter where “The

Streetwalker’s Price” was a life-preserving lesson. “A Gun in

the House” offers a sense of security and comfort, and

protection against intruders, but Constance testifies not all

the threat comes from outside the home.

Excerpt

Word Count: 12,750

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

| |

|

|

The stories in this eclectic trilogy are

unrelated, except for their setting at the end of year holiday

season. The first must be saddled with the based on true events

disclaimer; the next is related just the way it really happened;

and the last story is pure fantasy.

Excerpt

Word Count: 8000

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99 |

| |

|

|

The story opens with a very strange cargo for

an oxwagon driver—the comatose body of a woman whose passage is

paid by a man fearing for his life. When the driver takes on the

load, he also takes on unexpected adventure for everyone

involved on the long and perilous overland trip.

Excerpt

Word Count: 22900

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99 |

| |

|

|

Ever wish you could call back a promise you've

made? David Stone, American, has adopted South Africa as his

home and Marjie van der Leun as his lover. It's an on-again,

off-again affair, but during one of the on-again stages, David

made a commitment which would come back to haunt him. In a

reckless moment, David said he would kill for her. Now Marjie

wants to call in that favor.

The arrangement involves a lot of money and once David is "in

for a penny, he is in for a pound," as the saying goes.

The plot thickens, Marjie is prosecuted for the murder and David

thinks he has gotten away... until...

Excerpt

Word Count: 50000

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

| |

|

|

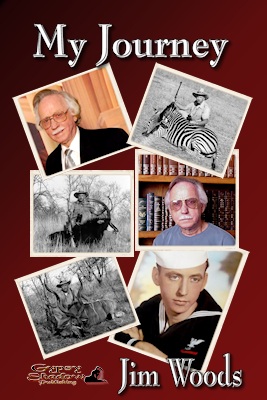

Jim Woods was a sports hunter writer,

outdoorsman and game hunter. Follow his journey from his early

beginnings in the Navy through many hunting adventures, both in

the Eastern and Western hemispheres as he searches for and bags

trophy game.

Excerpt

Word Count: 98600

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $5.99 |

| |

|

| Excerpts |

So You Want to be an Author? |

Introduction To The Real World Of Publishing

Acquisition Editors at the book publishing houses, and literary

agents, big and small, are overloaded with work. Thanks to the

computer age, thousands upon tens of thousands of manuscripts

are submitted to them every year, and the numbers continue to

grow. While the publishers are reducing their payrolls by

cutting down on staff just to stay afloat in a tenuous economy,

the agencies, many of which are single-staff proprietors, simply

cannot handle the increase of prospective work that crosses

their transoms. Reduced editorial staffs and inundated agents

coupled with the ever-increasing numbers of submissions to those

offices have resulted in a logjam of manuscripts that seems to

grow in quantum leaps.

It doesn’t take much of a perceived problem with a manuscript to

cause it to be tossed out as unworthy of the editor or agent’s

already crowded work schedule; they look for reasons to diminish

the backlog. It may be the cover letter; it could be the paper

stock on which the manuscript is printed; but more than likely

it’s the grammar, punctuation, spelling, usage and structure of

the first two or three pages... and that’s all that will ever

be read!

The first strategy in combating the problem, to allow the editor

or agent to get further into the story to find out how really

great it is, is to ensure that grammar, punctuation, spelling,

usage and structure are as perfect as they can be made to be, by

double and triple pre-editing before submitting the manuscript.

We’re not talking style or storyline here; no amount of diligent

copy-editing will build a stronger plot or develop more

interesting characters. Those must come first with talent

(which, of course, we all have in abundance), then guidance from

qualified instructors and critics (not your spouse or best

friend), and then the tedious re-write(s).

It could appear to some that the answer to getting published is

simply to circumvent the overcrowded, overworked system, and

become your own publisher. The proliferation of information

technology has spawned numerous avenues for self-publishing.

According to which publishing newsletter or website to which you

subscribe, there are perhaps half a million or several million

self-published or vanity-published or web-published book titles

on the market. However, the buying public can be just as

critical if not more so than the professional editor or agent. A

poorly done book, poorly written and poorly edited, will quickly

get the bad name that will inhibit future sales. Self-publishing

is not altogether an ill-conceived idea, but putting out a

nonprofessional book, regardless of the publication and

distribution media, is bad for the industry and the author.

Subsequent sectors in this book will offer tips and insights on,

and examples of, those little glitches and gremlins that can

turn an editor or publisher away from your own potentially great

article, short story or novel. Of course, any advice treatment

must include a disclaimer:

This book is not an English, grammar, spelling or punctuation

textbook for the classroom. It does, however, serve as a useful

adjunct to those textbooks, and reflects the practical side to

all those literary disciplines as viewed by an author/editor who

has worked both sides of the editorial desk for a lifetime.

Teaching professionals will view the lessons presented here as

incomplete, and that would be true if it were intended to be a

course-study textbook. It does not pretend to contain all the

answers to writing in the English language, but rather is

designed, by use of examples and referral to the author’s

personal experiences as both editor and author, to make writers

think on their own and produce manuscripts less likely to be

rejected prematurely. If you remember no other rule of

commercial writing, it is this: The Editor is always right.

|

|

Back to So You Want to be an Author? |

Hits and Misses |

Honk If You Love Geese

Choosing a favorite big game species is a difficult and

arbitrary decision for me. My selection could be swayed by the

latest daydream inspired by one of my trophy mounts on the wall,

or by one of my rifles that I associate with a particular hunt.

I might vacillate between an African species that I have

collected several times, or one that almost collected me; or I

might settle on the noble western mule deer that I have loved to

hunt. It would be a tough choice. But among the birds,

everything comes second to geese.

For no good reason that I can offer, I do not have a taxidermy

mount of a Canada goose, although I favor those mounts with

giant wings cupped for landing. The only tangible goose

decoration in my writing work space is a pair of carved birds;

not decoys, but miniatures carved of fir and not painted, just

the natural color of the wood.

What makes them special is that they were fashioned by a Cree

Indian, carved over several evenings during the winter freeze

that imprisons the far reaches of Ontario, and finished to

splinterless perfection by being scraped with broken glass. Not

that the Indians could not get sandpaper if they wished it; on

James Bay where the Crees live, the historic Hudson Bay store

still supplies all the necessities of life, and that could

include sandpaper. Why broken glass then, instead of sandpaper?

Because they have broken glass, and materials on hand are to be

used. It could be called conservation and recycling.

Geese are godlike to the Crees. Tribal hunters take them by the

boatload under the native subsistence laws of Canada, and the

tribe does subsist on geese for the entire winter when the

waterways freeze over. For a people normally given to hard work,

days of forced inactivity produce some native art of exceptional

merit, including my toy geese.

I do love the big birds. If there is a greater thrill than a

flight of geese lifting off the water and flying past my blind,

I haven’t experienced it yet. It’s exciting to have them pass

close enough to get off a shot, and a pure satisfaction to bring

one or two down from the flight, but many have been the times I

was content to watch them pass without my ever slapping a

trigger.

It’s another thrill to have the grand creatures come to your

call and decoys. In fact, I’m not sure I could say whether

sitting in a morning blind waiting for and experiencing the

liftoff and formation or turning the birds from a high flight by

a coaxing call is the more exciting.

Much of my sitting in blinds waiting for the over-flights has

been on Maryland’s eastern shore of the Chesapeake. There is

little in the United States to compare with the Chesapeake when

it comes to geese. James Michener captured the spell of the

geese in the novel, Chesapeake, and to have written that novel,

he had to have experienced the flights over Chesapeake Bay. If I

were to build a permanent waterfowl blind on Chesapeake Bay, I’d

outfit it with a pew for a bench, for at no time do I feel more

in church than when the geese fly.

I was fortunate to have hunted the Chesapeake without having to

compete for space along the public accesses, and without the

necessity of joining one of the expensive private clubs that

control much of the admittance to the waterways. All my

Chesapeake experience has been as a guest of Remington Farms.

Remington, the arms and ammunition people, at the time operated

Remington Farms on the bay. The farm, which included a wetlands

sanctuary, was a virtual field laboratory for wildlife habitat

and related sciences. It was common to observe university

students and wildlife biologists at work on Remington Farms, and

not only on waterfowl projects but also on those associated with

deer and small game, and with general agricultural-improvement

methods that benefited farmers nationwide.

In addition, some limited hunting was authorized, controlled

hunting being a prime wildlife conservation tool. Remington

utilized the setting to host outdoors writers from time-to-time

for introduction of the company’s new firearms products. Those

sessions usually included a couple of days of hunting. It was

during these sessions on Remington Farms that I enjoyed my

well-remembered Chesapeake Bay goose hunting. At all times when

hunting on those press junkets, the Chesapeake geese were

zealously protected, by the federal waterfowl regulations, those

of the state of Maryland, and perhaps most rigidly of all by the

caring custodians of Remington Farms.

The geese at Remington Farms do not originate at Chesapeake Bay

but only stop there en route to wherever their instincts take

them on their annual journeys. The geese moving down the

Atlantic and Mississippi flyways, and perhaps some that take the

Central Flyway as well, gather for their odyssey at James Bay,

the southern projection of Hudson Bay between Ontario and

Quebec. The birds don’t necessarily originate there either. Most

of them are spread much farther north, summering all along the

northernmost perimeter of Canada, including frigid Victoria and

Baffin islands and all of the Arctic landfalls.

|

|

Back to Hits and Misses |

Women with Weapons |

“What do you mean,” she screamed, “there’s nothing the police

can do? He stole my money! Don’t you understand? My husband took

all my money from my IRA and he’s gone. Run off. With my money;

a hundred thousand dollars! That’s robbery. He’s a thief! Why

can’t you do something?”

“Ma’am, please control yourself. Shouting and abuse don’t help

matters. There is no indication of theft here. Now I suggest you

take this up with your bank, or perhaps your lawyer can do

something for you as a civil matter, but there is nothing

pointing to a crime in what you’ve told us. I’m sorry, Missus

Tucker, this simply is not a police matter.”

Marlene Tucker was shocked beyond tears. She had to make the

trip to Missouri; Aunt Catherine became ill and no other family

member could, or would, make the effort to attend her. First the

hospital in Kansas City for four days and then more than two

weeks at Aunt Catherine’s home, nursing her back to

self-sufficiency. Bedpan duty. Nursemaid. Cook. Housekeeper.

Marlene didn’t mind, at first; she loved her aunt. Now she hated

her.

Philip telephoned her daily, or she him, and sometimes both

ways. He was supportive, or seemed so. Said he missed her. She

assured him she’d be home soon, but had to be truthful; her care

to Aunt Catherine was going to run into weeks, maybe even a

month. He’d muddle through, Philip assured her, “You take care

of Aunt Catherine; I’ll take care of things here.”

Oh, he took care of things all right! Philip hadn’t called her

at her aunt’s home for the past three days, and he didn’t answer

when she called him. Marlene was fearful Philip had an accident,

or a heart attack. Finally she had to leave her aunt on her own

and she rushed home to Portland expecting the worst—and found

it, but not at all what she dreaded. Philip was not at the

house. The houseplants were dry and wilted. Philip’s car was in

the garage; his key ring on the hook near the front door. The

front door was not locked; the security alarm was not set.

Marlene could not say what prompted her to look in Philip’s

closet. Some of his clothes remained, but most of them were

gone. Philip was gone. She went to his underwear and socks

drawers. Mostly empty. Fear turned to trembling understanding,

to anger, to rage, to utter shock. Philip had left her like a

thief in the night. The unspoken phrase ran through her tortured

mind and triggered her to action.

Noting the time, and realizing the bank was closed for the day,

Marlene went to her computer and accessed her account. She was

relieved to note the checking account balance was more or less

normal, close to the four thousand dollars they always tried to

keep for operating expenses and small emergencies. Then she

scrolled down to recent activity, and terrified understanding

came to her in a shockwave. Three days ago, some six hundred and

fifty thousand dollars had been withdrawn. A week before, two

super large deposits were made, totaling a similar amount. The

sonofabitch! He had cashed out both their retirement accounts,

nearly a hundred thousand in hers and more in his, more than

five hundred thousand. He got away with over six hundred

thousand dollars! But why would he do this? Where would he go?

Marlene had nowhere to go but to the police. She called 911.

The dispatcher calmed Marlene as best she could and upon

understanding the extent of Marlene’s hysterical trauma,

suggested an officer on the scene was not the remedy, and coaxed

Marlene to come down to the station and talk with someone in

person. The dispatcher assured Marlene she would have an officer

apprised of the situation and Marlene would be expected. But the

police detective, sympathetic but firm, turned her away.

|

|

Back to Women with Weapons |

Toys, Lights and Trinkets |

Ghost Breakers (third story in book)

The wizened old witchdoctor in Zimbabwe had been right all

along. Although he obviously did not know us—my wife Anne and

me—he was much too believable in his wisdom. He somehow knew

things about us he had no need or right to know, but we

solicited the interview. No one tricked or coerced us to consult

him, so we listened to him. Anne and I were a lot younger then,

and at the same age, and on one of our several safaris in

southern Africa when the old Mashona gentleman consulted the

bits of carefully arranged chips of mystic bone that spoke to

him. One of his revelations predicted Anne would live ten years

longer than me. He was right on; I crossed over a full decade

before Anne joined me once again. And while it is true, there is

a time to die, Anne’s family would take her passing especially

hard, it coming so near Christmas—a time that should be reserved

for happy memories.

Even though I left earlier, and fittingly, in the fall of the

season and the autumn of my time, I couldn’t stay away. Our

lifetime together was too strong in the physical world to be

fractured, simply because I happened to be deceased. I hung

around the house to keep Anne company. Admittedly, a few friends

and even family tittered behind her back about her carrying on

conversations with me. We tried to pay no attention, and really

were not offended. In fact. it was amusing to us knowing what

was going on and they only could guess, and speculate that Mom

or Grandma, depending on which generation was the questioning

source, was hanging on to the cusp of dementia. Anne and I held

a lifetime of memories to recall between ourselves, and we

untiringly relived and talked them over.

Anne and I stood together, hand-in-hand, at her funeral service.

Being unseen, except to one another, made it easy for us to get

a front row view. The Anne beside me was beautifully young, and

she noted the same about me. Shucks, I don’t mean she said I was

beautiful, just she thought me young and in my prime. We both

agreed the body on display the day before at the funeral home

was not Anne, but some wrinkled lady who still showed evidence

of having been beautiful, and if we examined her closely, my

red-haired Anne did show through. Everyone in attendance had

nothing but kind words for my bride, as they did for me as well,

ten years back. The difference was at my wake; everyone still

talked respectfully about me, which was to be expected since

Anne was present for all the comments and conversations. That

condition changed somewhat drastically at the after-service

gathering in remembrance of Anne. It was our granddaughter,

Rochelle, whom we both loved, who opened the less than lovable

exchange with her mother, Anne’s only child, Charlene, from her

first marriage which went awry before I came into her life.

<<>>

“What are you going to do with all of Grandmother’s crap?”

“I’m surprised you’d say something like that. Mom and Dad may

have accumulated a lot of things over their lives and travels,

but certainly no crap. They always bought quality.”

Good for you, daughter, Paxton telepathed. You tell her!

“Sorry, I didn’t really mean it that way. They just have so much

stuff. How do you even start disposing of it all?”

“Let’s not rush into disposing of anything. I still have to

locate the will, although Mom has told me everything goes to me

and I’m listed as executor.”

What do you mean, have to locate the will? It’s right where I

told you it would be, in the safe, and the safe combination is

pasted behind that framed certificate in my library.

|

|

Back to Toys. Lights and Trinkets |

Oxwagon |

“Are you sure she’s alive? She looks dead to me and I don’t

transport dead bodies for any price. For that matter I don’t

take passengers either, so we have nothing to discuss. No deal.”

“Verdoem, man. Cover her back up; I don’t even want to look at

her again. I’ve got to get rid of this woman. She’s driving me

crazy and she tried to kill me.”

“Then why didn’t you just kill her? If she tried to kill you,

you’d be justified. Unless, of course, she had reason to. But

actually, I don’t want to know. I’m just not taking her on this

trek.”

“Man, you’re in the transport business, and this is cargo I need

transported. Why can’t you take my business? I’ll pay to have

her transported to Fort Salisbury. Tell me, what are your

rates?”

“But I do not take passengers, much less a woman. This is hard

country. We barely survive it ourselves, what with the rains,

the mud and the fever. And we lose oxen on every trek, if not to

the lions, then to their exertion of pulling too much weight

over bad country. Their strong hearts simply fail, or they break

a leg and we have to shoot them. And when they get tired and

cranky they fight among themselves. That’s why we take along

extra teams of the animals. We lose too many on a trek. Don’t

you understand? This trek is too hard as it is. No passengers to

make it even worse!”

“Verdoem, Clayworth, this woman is not fit to be called a

passenger. She’s freight, pure and simple. And if she does not

survive the trip, I don’t care. Dump her off just by the side of

the road as you would any other damaged freight. So, tell me.

What is your rate to Fort Salisbury?”

“See here, now, Hannes. You know my rates very well. They’re the

same as any other transporter’s. This won’t do you any good, but

Johannesburg to Fort Salisbury is a three-leg trek. The first

leg is from Johannesburg to Palachwe; the next is to Bulawayo;

and the final leg is on to Fort Salisbury. My rates are

twenty-five shillings per hundredweight, per leg. That’s

seventy-five shillings. Man, you could buy her a salted horse

for that if she wanted to go to Fort Salisbury and she could

join a train on her own.”

“I never said she wanted to go to Fort Salisbury. I want her as

far away as I can put her and Fort Salisbury fills that bill.

Look, I know she’s swaarly, more than a hundredweight. I’ll

double your price. One hundred and fifty shillings, a shilling

for every pound, to take her with you all the way to Fort

Salisbury. Dump her off there and she’ll never find her way back

here again. What do you say?”

“I say no, just as I’ve been trying to tell you. No passengers.

Passengers have to eat and the trip takes twenty to thirty weeks

and that’s if we have fair weather. That’s a lot of extra food

to carry or find along the way. A man could be useful on a long

trek, but not a woman. A man can stand night watch. He can chop

firewood. He can wade the mud to pull the trek-oxes through. A

woman. Bah! On a wagon trek she’s good for one thing and one

thing only. And not good at all when my partner and I would

share her. No. I won’t do it. Take her away. I have to inspan

and get on my way. Sunlight is a wasting.”

“Now see here, Clayworth. I’ll pay you triple. Two hundred and

twenty-five shillings to take this problem off my hands and the

load off my mind. What do you say?”

Jerrick Clayworth, grim and tight-lipped, forced himself to hold

back lashing out again to the Afrikaner, Hannes Crouse. He

considered the offer of two hundred and twenty-five shillings,

more than eleven pounds, more than enough to pay for a

replacement ox when he lost one, as he was sure to do somewhere,

sometime on this trek. And if the woman died along the way, or

went on her own way once they were a few days out of

Johannesburg, then so much the better. But is she really alive?

Jerrick lifted the woven-reed lid from the deep and sturdy woven

grass basket once again for a confirming examination. The woman

was dressed in man’s breeches and boots, with a shirt top that

was male as well. She made no sound. He bent low to inspect her,

noting no bleeding wounds, but more importantly no smell of

death about her; an earthy odor but certainly not dead.

“How did she get in this condition? What’s the matter with her?

Why is she unconscious and how long has she been this way?”

“She’s just knocked out for a while. She’ll come around.”

“What did you give her?”

“I got the potion from a sangoma. I don’t actually know what’s

in it.”

“Then how do you know she’ll come out of it?”

“The old teef told me she would, and if she don’t, I’ll wring

that witch’s scrawny black neck and take back the two goats I

paid her.”

“Well she don’t look dead, but if she does come out she’s going

to get really messy in short order when her body starts to

function again. We’ll have to get her out of that basket. I’ll

spread a bullock hide to lay her on so she don’t piss or crap

all over my goods when she wakes up.”

“Danke, Clayworth. Here, I’ll help you with her.”

“Not so fast. I’ll take the shillings first; otherwise she stays

in the basket and goes home with you instead of on the trail

with me.”

Grumbling, Hannes counted out two hundred and twenty-five silver

shillings, and in so doing, emptied the bag. Jerrick noted and

realized Hannes knew all along how much he would have to pay and

was prepared with just the right amount. Hannes cupped the

coins, returned them to the pouch and handed it over to Jerrick.

Together the two men spread the hide over the crates and

baskets, and stretched the still inert figure on it.

“Does she have a name?’

“I always called her Gertie. Gerta, I suppose?”

“And her surname? Hell, man if she dies on me I have to be able

to burn a name on the crossed sticks. I couldn’t leave her for

the animals.”

“Verdoem, man. Don’t bother to dig the ground for her. As far as

I know even she doesn’t know her father’s name or even who he

was. She’s just Gertie and the hyenas won’t check her pedigree.”

|

|

Back to Oxwagon |

The Outlander |

Chapter One

David Stone seldom went to sleep at night without acknowledging

he was perhaps the most fortunate bachelor on Earth. After

college in California, he practically had fallen into his job, a

well-paid management position, allowing him to return to the

country of his birth, South Africa, a locale of which he held

scant actual memory. Others’ recollections passed on to him,

combined with old photographs, triggered false memories of a

father he had never known. He knew now his father had been a

professional hunter, a safari operator. It was rare for an

American to hold such a position in this country and David

treated the knowledge as a birthright of near royalty for

himself. David had been on safari several times, enjoyed an

impressive salary and social position, and all the female

attention that money could buy. Life indeed was good; David

Stone had everything to live for.

David stirred and groaned at the first summons from the distant

kitchen telephone. At the second signal he tossed aside the

light comforter and swung his long frame upright, legs dangling

over the side of the king-size bed. By the third insistent

chirp, he was awake enough to curse his boss in California, who

refused to authorize the trivial expense of adding a second

instrument for the bedroom of the company-leased condominium in

Durban.

Alex Becker, absentee owner of PCI (Pty) Ltd, in addition to

being cheap about minor expenses, also demanded the full

attention of any employee who happened to be the object of his

thoughts at any particular time. He reasoned with the nine-hour

time differential between the United States west coast and South

Africa, a call placed to South Africa during his local business

hours stood a good chance of finding his area manager in bed

instead of in the office or out on the road. He wouldn’t

tolerate sleep-befuddled answers to his questions, so his scheme

was to ensure David always had to be sufficiently awake to find

the telephone at the other end of the house, and therefore be

alert enough to reel off all the correct responses.

David once again resolved to put in the additional phone at his

own expense, but knew that he wouldn’t, because Alex would raise

Holy Hell about it when he commandeered the guest bedroom on his

next unannounced visit. As much as he enjoyed thinking about

crossing Alex, he knew that he would not. His position as almost

total controller of the South Africa office provided him a very

comfortable, even lavish, lifestyle he wouldn’t jeopardize. He

was more or less fully functional when he snatched up the

handset.

“Private Computers International,” he puffed into the

instrument. “This is David Stone.”

The call had to be from Alex this time of night, David was

certain, and his absentee employer demanded formal business

telephone protocol. A clerk from the office who stayed late with

David one evening, then on until morning, had been helpful in

answering the telephone in order to let David continue his

recovering slumber. Her pleasant and sensual hallo sounded

anything but businesslike to Alex, and she was instantly

dismissed from her job and David came perilously close to being

yanked back to California. Since then, David’s guests were

warned away from taking incoming calls and he was careful always

to be professional on the telephone, no matter what the time of

day or night.

“Dave? This is Marjie.”

The voice jolted him. She didn’t have to say Marjie Who. David

remembered Marjie. When he first took the assignment in South

Africa three years before, he’d taken stock of the local talent

and identified Marjie as a sexy airhead. He was only half-right;

she was sexy. She also was a very smart engineer who’d developed

the power module allowing the PCI computer to work on the

peculiar 50-cycle, 230-volt electricity produced and distributed

by South Africa’s national electric power company, Eskom. Marjie

worked for Eskom but, thanks to some expensive and persuasive

encouragement from Alex Becker, her efforts had been

instrumental in opening the Southern African market to PCI

immediately after the post-apartheid government took over in

1994, when foreign investment in the country once again became

an attractive proposition. PCI was able to beat the competition

to the marketplace by several months, and still held onto that

advantage.

David had been the recipient of a Masters fellowship sponsored

by PCI, and his brilliant thesis on marketing opportunities in

Third World countries won him the managerial assignment with PCI

in South Africa. PCI joined with Eskom in a

politically-motivated venture to bring technology to the

underdeveloped nations of sub-Saharan Africa. Thereafter, at the

local implementation level, David and Alex together coordinated

closely with Marjie, a working threesome by day and, after

hours, one or the other of them a playful pair with Margie,

according to her fancy.

Marjie permitted both PCI-exec Alex and second-in-command David

to court her, but she’d been promoted to an assignment to

electrify the rural northern Transvaal a couple of years ago,

and David had lost contact with her. Marjie’s departure

apparently had been Alex’s reason for the abrupt decision to

wrap up his personal control over the South Africa operation,

ceremoniously turning it over to David and immediately returning

to the company’s home base in California. Now Marjie was back in

David’s life, and his groin ached pleasantly in remembrance of

their times together... and Alex was not hovering nearby to

claim a share of her.

“Marjie! How’ve you been? Where are you? What’s going on with

you?” He wanted to say something clever and smooth, but felt

tongue-tied and angry with himself because he couldn’t control

his thoughts or his voice. What kind of schoolboy must she think

I am? he wondered, but Marjie cut in with her assurances of how

much she missed him. She explained that she had gone back to the

family home in Cape Town for a while after her project in the

north was finished. She had just returned to her own home in

Pietersburg and wanted, no needed, to see him.

“Davie, do you remember when you...” she struggled for the

words, “offered to eind die lewe of someone for me if I ever

needed it? Well, I need to talk to you about that now. There’s

twenty thousand in it for you. Can you come?”

Wheeew, he blew silently, and was quiet for just an instant too

long. Marjie was necessarily fluent in English as the language

of commerce and technology in South Africa as in most of the

rest of the world, but in this very personal turmoil she

reverted to her traditional language. She had used the

Afrikaans, end the life. Murder someone!

“Daaave,” she came back impatiently, “didn’t you mean it?”

He remembered. When she found out he was keen on firearms, she

pursued him with pleas to make her a shooter, and he enjoyed the

attention. He instructed her in the use of several guns, from

the FN-FAL battle rifle used by the South African military to

his favorite personal handgun, the Browning Hi-Power

nine-millimeter pistol. She was an eager pupil. The excitement

of their shooting sessions carried over to the bedroom. Once, he

teased that if she ever needed anyone removed, she had only to

call on him. Her thrill at the prospect of him killing someone

at her direction moved Marjie to even greater appreciation.

“Yes, I meant it,” he struggled to assure her. He’d lost her

once. Now with the prospect of having her back, he wasn’t about

to give her up again over some silly notion she harbored about

killing someone. He had spent only a few weeks collectively in

the United States over the past three years of being posted in

South Africa and had become completely at ease with the local

currency, rands. However, he still converted to dollars to know

what prices were in real money. Twenty thousand rands was

roughly five thousand dollars. “I can take care of that for you,

but it’ll cost fifty thousand. Haven’t you heard about

inflation?”

“Done!” she exulted. “I would have given you a hundred!”

Hey, she’s serious! What am I letting myself in for? “Just who

am I supposed to kill?”

“I don’t want to talk about this kind of business on the phone.

Let’s meet at the Carlton. I’ll drive in and get a suite where

we can talk in private. Can you fly up tonight?”

Durban—almost six hundred kilometers from Johannesburg, he

computed quickly; Margie’s base in Pietersburg about half that.

“No, I’ll drive up in the morning. In fact, I’ll leave in three

or four hours and be there in the early afternoon. I’ll get the

hotel and call you at home and we can meet there later that

evening. What’s your phone?”

Now it was her turn to hesitate. Clearly she wanted to control

the venue, but eventually she gave her grudging approval to the

plan. She stumbled over the telephone number as though having

difficulty remembering it, then blurted out the four digits. As

David wrote them down on his phone-side pad, he automatically

added the area prefix for Pietersburg. “I’ll ring you up from

the city,” he said hoarsely, and hung up.

No, he thought, I’ll ring you up right now! Then, halfway

through dialing he slammed down the receiver. Sprinting to the

bedroom, he pulled on the navy-blue sweatpants he’d laid out in

preparation for his early-morning roadwork regimen—eight

kilometers at a dedicated runner’s measured pace designed to

cover the distance in an easy half-hour—then struggled into the

matching pullover top emblazoned with Santa Clara in yellow

script across the chest, and Broncos on the back He snatched his

keys, change and handkerchief from the dresser-top valet and

jammed them into the muff pocket, then pulled on his tackies,

stuffed the hanging laces into the shoes against his bare feet

and rushed to the carport. The Mercedes responded to the turn of

the key and squealed down the drive, then onto the street that

would take him over to Windemere Plaza and the public phone.

If I’m right, he thought, she will have to go to the post office

to find a coin phone in Pietersburg. Having driven extensively

over the past three years through the sparsely settled Transvaal

Province in presenting PCI’s computer system to potential

clients—the exception to spotty populations that characterized

the rural province being the Johannesburg/Pretoria megaplex—he

knew that the post offices in the smaller towns were the only

places to find public telephones this time of night, and

generally they were located in the seedier parts of downtown.

David reasoned that Marjie would have to drive several minutes,

perhaps even a quarter of an hour or more, to get from the

upscale Ster Park neighborhood where she lived to the only post

office in Pietersburg, and her return trip might give him enough

time to verify she did not call from her personal telephone. As

he wheeled into the plaza parking lot, he spied the lighted

phone pod and was relieved to note that it was not in use.

Another problem with the public telephones, as he and all the

whites were aware, was the instruments were normally tied up by

the blacks who did not have phones at home; they monopolized

them for hours. This time of early morning, even the

street-blacks were not hanging around the telephone. His first

thought, since the cubicle was unoccupied, was he would find

only the broken and frayed, dangling cable but he was relieved

again when he found the instrument, to be in working order.

Using his crisp, white handkerchief, he dry-sanitized the

assumed-to-be-contaminated receiver and mouthpiece with a couple

of determined rubs, and then tossed the streaked cloth in the

nearby wire trash bin. He dropped a two-rand piece in the coin

slot and determinedly punched-in the regional code for

Pietersburg and then the home number Marjie had given him. It

rang on the other end three times before an answering machine

responded in her purring voice. Okay, he reasoned, she did not

call from her home. She’s making sure, as I suspected, no record

of the call from her telephone could ever be traced to my

number. I’ll have to be just as careful from my end.

The leisurely drive through the few blocks to his neighborhood

gave him time to muse over just how he would stay a step ahead

of the beautiful lady Marjie while also getting her into his

bed. Back at the condominium, he dropped into that friendless

bed still fully clothed, with Marjie, not at all so encumbered,

the prime focus of his schemes and fantasies.

Fighting to clear his head of drowsiness just half an hour ago,

he found now he could not sleep. He stripped off the jogging

clothes, ran the shower hot while he shaved, then lunged into

the revitalizing spray and steam. In the kitchen, he switched

the automatic coffee pot from his normal wake-up time to ON, and

watched gratefully as the life-giving drip started almost

instantly. Then he wet-tracked across the gray stone-textured

tile to the bedroom. As he draped the towel across a

maroon-upholstered chair he wondered, what does one wear when

negotiating a hit contract?

After two cups of coffee, brewed to his still American

taste—South Africa offered many culinary pleasures, but the

provincials simply could not make decent coffee—and half a box

of Baker’s Tennis Biscuits, one of those off-the-shelf culinary

pleasures—he dressed for the drive to Johannesburg.

|

|

Back to The Outlander |

My Journey |

A Long Walk Home

This account of my birth is enhanced family verbal

history—enhanced because I don’t know precisely what dialogue

was spoken, although the gist of it is faithful to what I’ve

been told. I’m not certain that my mother remembered exactly

either, and quite likely recalled and told it a bit differently

each time I heard it from her. However, the story is as I

remember it being told to me, and of course I have no personal

memory of the events.

“Virgull! [My father, Virgil Neff Woods] Ah kain’t go no

futher!”

Already some fifteen steps ahead of her, he deliberately took

two more as though he didn’t hear, and then disgustedly set down

the two battered and mismatched suitcases. He unslung the water

jug hanging by the rope loop from his shoulder, and turned to

face her.

Her streaked, blonde, straight, sweat-matted hair clung to her

colorless features. She hadn’t put on lipstick in four days.

Even her normally blue eyes were dusky gray.

The tattered sweater, once blue like her eyes, now faded by the

years and grayed by the dust filtering upward from her every

step, hung limply on her shoulders. The stretched sleeves

covered half of her hands so that only her fingers were exposed

below the frayed cuffs. She had needed the wrap in the coolness

of the morning when they started out just after first light. Now

at midday in mid-September, the Arkansas weather was steamy.

Still, it was easier to wear the sweater than to carry it and

the sniffling boy too.

Her dress once had been a bright flowered print. She traded and

coaxed cloth from neighbors until she had enough of the

multicolored flour sacks in the same pattern to make the only

maternity dress she had ever owned. She had worn it while

pregnant with the boy, now in her arms, two years ago.

Threadbare and almost bleached out, once again it stretched taut

across her swollen stomach. The soles of her flimsy sandals gave

way to the piercing of every pebble in the road, and her feet

were bruised and dirty.

“We can make six more miles today,” he objected gruffly, then

relented to the persuasion of her silent tears.

Under the refuge of a hickory tree just turning to yellow

alongside the grassy roadside ditch, he fished cigarette makings

from the bib pocket of his overalls. To conserve tobacco, he

packed the paper loosely from the Prince Albert can, twisted the

ends to keep the cherished narcotic in place, and then popped a

wooden match into flame under his grimy thumbnail. When the

paper flared and the tobacco glowed, he stuck the half-burned

match to the grass and twigs she had gathered for a cook-fire.

He appreciated the tree that sheltered them, but cursed the

forest around Hardy [Arkansas] that finally had run out, causing

the mill to shut down. It had been degrading for him to go

hat-in-hand to her sister’s family in Fort Smith, and beg to

stay on with them until he found another job. There should be

jobs. It was 1934; the Depression was turning around, the

nation’s economy on the way to recovery—Mister Roosevelt said

so. Then came the letter from his own sister Catherine [Pierce]

in Paducah [Kentucky] telling him that the Illinois Central Shop

was hiring—and paying forty cents an hour!

Paducah was three hundred miles away. Train fare was impossible

for them, so they set out afoot, and had been lucky with rides

while they walked along the main roads. They crossed the Ozark

Plateau in three days, sometimes hitching a ride on a wagon or

truck. They even slept under a roof every night; on the ground

huddled in their coats in abandoned or dilapidated barns, but at

least not out in the open. Now at Marked Tree, they turned

northeast through the Mississippi Valley to cut across the

corner of Missouri into western Kentucky. The main flow of

commerce moved in the tug-towed barges on the river, so the

surface roads through the region were lightly traveled. The

single car going in their direction passed with a blaring horn

and a flurry of dust. They had walked nine miles.

She untied the rope from around the heavier suitcase, and

removed the cast iron skillet and the battered aluminum pan that

long ago had lost its handle. Then she dug out the bag of flour

and measured a couple of handfuls into the pan. From the Clabber

Girl can, she added a pinch of baking powder, and lastly, a

sprinkle from the saltbox. She twirled the ingredients briefly

with her single tablespoon, and formed a depression in the

center of the mixture.

He pulled the cork from the jug of tepid, cloudy water reclaimed

from a farm pond back down the road, washed the dust from his

mouth with a swig, and handed her the bottle. She poured some

into a tin cup to give the fretful boy a drink, and then clucked

soothing endearments to quiet him, while she splashed more water

into the flour mixture. When it was stirred into a thin batter,

she used the same spoon to measure lard from the tin to the hot

skillet where it sizzled and smoked, and spooned three pools of

the batter into the skillet. She then retrieved the spatula he

had shaped and thinned from a broken board with his clasp knife

on their first night’s stopover.

After the batter was covered in bubbles over the entire top

surface, and the bubbles broke, she flipped the hoecakes over to

cook them through. The edges of the bread were burnt and crisp,

while the centers were plump and soft. When the first one was

done, she passed it to her husband. She turned her attention to

the boy, crumbling the next hoecake in a tin plate and pouring

syrup over the pieces from the almost empty Log Cabin can. Then

she mashed the bread into a gooey mixture and spoon-fed the boy.

She was snatching a bite of her own bread in between feeding the

boy when He demanded, “Don’t we have some of that baloney left?”

Setting her lunch aside, she probed once again into the kitchen

suitcase and produced a greasy paper package, and remembered the

meager feast of last night.

They agonized over the decision, but had spent a precious dime

for their first meat in three days. It was hard to wait as the

butcher sliced a few pieces from the cloth-wrapped sandwich

loaf. When the man realized how desperate was their hunger, he

rolled another sheet of butcher paper into a cone and filled it

with crackers from the barrel out in front of the counter. They

protested that they didn’t have money for crackers, too, but he

insisted that crackers were free with the purchase of bologna.

They carefully divided the meat and crackers into two portions

and put half away for the next day, even though what they

acquired was barely enough for one meal.

She unwrapped the package and gagged at the odor, and her eyes

brimmed at seeing the formerly fresh pink bologna now slimy and

tinged with green. The crackers, also closed up in the hot and

airless suitcase, had gone stale and soft. Her weeping turned to

near hysterics at the waste, and he stoically resolved not to

add to her misery. He wouldn’t voice the deserved accusation

that she should have known this would happen when he insisted

they not eat it all at one time. Besides, she cried at

everything these days.

She separated the crackers on the butcher paper in the forlorn

hope that they would dry in the air and perhaps serve as an

acceptable snack to pacify Bobby [My brother, Bobby Gordon

Woods] before the next meal, then solemnly fried the last of the

batter.

After another sip all around of the just barely drinkable water,

she started to repack the suitcase, because she knew that he

wouldn’t allow them to rest here for very long. As she twisted

around in her sitting position to stretch for the fry pan, she

felt a sharp, penetrating pain and screamed him out of his

musings of the good life to come. “Virgil! The baby’s coming!”

“Don’t be silly, Ethel Marie! [My mother, Ethel Marie

(Burns)Woods] You’re just upset over that damned baloney. You’re

not due for two weeks and we’ll be at Cat’s way ‘fore then.”

“No! It’s coming. I know it is and it hurts! You’ve got to help

me!” Her panic was real and contagious.

“What can I do?” Now, scared at his inadequacy, he was yelling

at her. She had no right to involve him in this business that

was her doing.

“Get the coats... and the boy’s diapers!”

|

|

Back to My Journey |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| top |

|